Emotions of Normal People: Book Summary

Emotions of Normal People was written by William Moulton Marston.

Published in 1929, Emotions of Normal People provides a theory for how and why people behave the way they do. Marston’s book would eventually become the foundation of DISC theory.

It’s important to clarify, Marston did not use his theory to create a DISC assessment or profile. In fact, he was determined to use it as a way to help improve his lie-detector.

Instead, that would happen when Dr. John Geier used Marston’s book as the backbone theory for his first personality assessment, the Personal Profile System, over 20 years after Marston’s death. Dr. Geier would go on to establish Performax, which eventually became Inscape Publishing, which was later acquired by John Wiley & Sons.

Geier stated that Marston’s book “laid the groundwork when he described the primary emotions and drew up terms which might be used to measure those factors.”

Additionally, it’s important to mention that Geir drastically altered Marston’s theory. What we know as DiSC today differs from what Marston wrote in 1929. Yet, Emotions of Normal People can still adequately describe the difference in energy we can all feel in ourselves and how we perceive others.

This summary doesn’t capture the entire book. Instead, it focuses on the essential parts that are relevant to DISC.

Emotions of Normal People: Summary

William Moulton Marston asks the reader, “Are you normal?” Ultimately, Marston believes that you are.

What makes you act ‘abnormal’ is ultimately due to your fears. Marston contends that many psychologists study abnormal fears (behaviors), but his book will focus on the emotions that make us feel pleasant and harmonious.

Marston provides a story from his childhood to help make a distinction between ‘normal emotions’ and fear. He recounts a story from his youth that he was bullied by a local child threatening him with an airgun.

Marston felt anguished about seeing the bully again because he might get shot. When he told his mother what was happening, Marston’s mother directed him to face the boy and not fight him unless the boy tried to shoot Marston. Ultimately, when Marston confronted the bully, the bully didn’t attack.

Marston’s fear didn’t give him the strength to confront the boy. Instead, it was the combination of the ‘emotion’ of dominance from his Mother and Marston’s ‘emotion’ of submissiveness (to his mother) that gave him the strength to face the bully.

This experience shaped Marston’s perspective of energy and how it affects our consciousness.

Materialism, Vitalism, and Psychology and its effect on Marston’s theory of Consciousness

Marston believed that the classifications and causations discovered through science are pushed by the scientist’s self-interests that conduct the research. Essentially, contemporary scientists research topics and conclude based on their own biases. Marston separates contemporary scientists into two groups: materialistic and vitalistic:

- Materialists believe that “science is the study and exposition of material causation. “Material” means “less complex forms of energy.” Therefore, true science is only the study of the influence of simpler energy units upon more complex energy units.” These scientists are less interested in imagining that there exists any other type of cause or causations.

- Vitalists often take prior assumptions and then find facts to fit their assumptions. Vitalist works often show hierarchies in life. The idea that ‘God made us in His image’ is often evident and places humans at the top of ‘life’s hierarchy’. Vitalists believe that higher energy forms are more complex than organic matter.

Marston uses the example of a plant growing in soil to help describe how both vitalist and materialist causations are shown as proof for how a plant grows. Science proves that the soil delivers a continuous series of chemical stimuli to the plant (materialist). The plant’s reaction to the chemicals is simply part of its own inherent nature (vitalist). Both vitalism and materialism provide a foundation on how to understand the biology of a plant.

However, this type of scientific causation doesn’t offer a way to view more complex topics such as consciousness. Marston writes that “[Humans] are entirely independent of, and influential over, the environmental stimuli which initially call into being [their responses]”.

Marston praises Psychology because it is a new science. Marston believes that psychologists tacitly or explicitly assume that consciousness is a manifestation of energy that exists and reacts as a unit separate from mere intra-neuronic disturbances. There are many individuals with unique types of work to help define and understand consciousness:

- Psycho-Physiologists – investigators who are trying to make careful laboratory measures of intrabody changes. Specifically, they are trying to describe specific types of consciousness based on physiological changes.

- Mental-Tester-Statisticians – these individuals are responsible for providing statistical testing for many psychological problems. Marston sees these individuals creating tests that prove vitalistic-type causes of the behaviors that are measured.

- Behaviorists – Behaviorists are grounded in the work of John B. Watson. They work to understand the behavior or activities of the human being. Marston believes that behavioralists are not concerned with consciousness from human behavior and activity.

- Psycho-Analysts – Marston finds that the psycho-analysts seem to take a special interest in the control which various conflicting and distorted elements of consciousness exercise over human conduct. Marston believes that if psycho-analysts take their findings one step further, they will arrive at the conclusion that libido turns into a form of unconscious, physical, or physiological energy. If this is true, then their analytical system must be regarded as mechanistic.

Marston surmises each section of psychology by saying, “Psychologists who seek to make simultaneous laboratory examinations of consciousness … are usually interested equally in mechanistic-type causes and vitalistic-type causes.” Marston hopes that psychologists will “manifest a little more boldness in the causal interpretation of their results once consciousness is definitely recognized as a form of physical energy.” Marston states that his research into the Psychology of emotion is looking to describe ‘affective consciousness.’

In other words, how does our consciousness react based on environmental stimulation?

Emotions of Normal People and the Phenomena of Consciousness

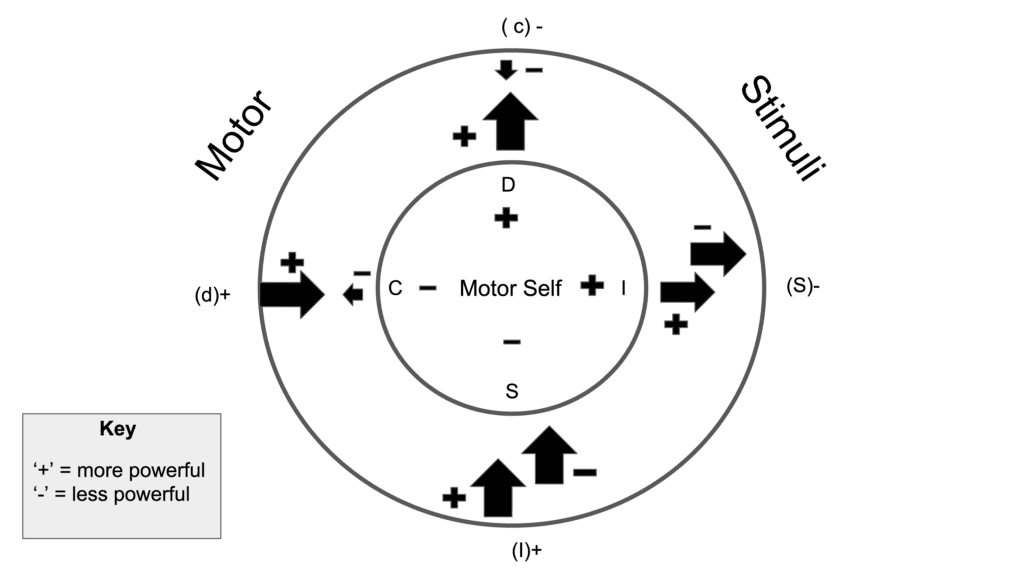

Figure 1.1 - Marston's model of active and passive components.

Marston believes that the answer to “What is consciousness” is often answered in a way that doesn’t really prove that consciousness exists. Behaviorists explain the existence of consciousness by saying, ‘everyone knows what consciousness is because everyone is conscious.’ Unfortunately, this doesn’t really explain what consciousness is.

Marston provides evidence that scientific instruments are available to detect waves, electric currents, and nerve impulses. Essentially, there is observable evidence of ‘consciousness’ producing force over physical elements.

Figure 1.1 represents a typography for how our responses are classified based on third party ‘forces’ we interact with. The ‘+’ and ‘-‘ represent the level of force both an individual and a ‘outside stimuli’ (person, group, situation etc.) use in an interaction. The letters represent the Marston’s emotional response classification:

- D – Dominance

- I – Inducement

- S – Submission

- C – Compliance

Marston goes on to clarify the situational evidence for each emotional response.

Dominance Emotion

Marston outlines 10 different forms of proof for the ‘dominance’ behavior which sums up as having the following elements:

- An antagonistic motor stimulus of less intensity than the motor self

- A dominant type of response evoked by this type of stimulus

- An increase in the strength of the motor self equal to the intensity of the opposition stimulus

Marston moves to provide further evidence of ‘dominance’ behavior in children. He shows how children respond to their environments in either a dominant or a compliant manner. Children who feel power over their environment will react with rage or control. Marston outlines how dominance can be viewed in different situations. What is particularly interesting is that Marston doesn’t see gender in dominant behavior. Marston believed that women’s dominance is ‘nearly on par with that of men.’ In Marston’s view, dominant behavior is evoked when a person feels power over their environment.

Marston expands on his idea of dominant behaviors over the environment. Marston states that “if the dominance response is successful, it will contain a larger comparative percentage of pleasantness at the end than it did at the beginning.”This feeling of pleasantness will only go away if the dominance response is met with an equally dominant opponent.

Characteristics of the Dominance emotion:

Marston lists a series of words and descriptions that he feels characterize each emotion for each emotion. Here are the words that he associates with Dominance: “ego-emotion,” “aggressiveness,” “fury,” “rage,” “self-assertion,” “initiative,” “will,” “determination,” “high spirit,” “self-seeking,” “courage,” “nerve,” “boldness,” “dare-devilry.”

Compliance Emotion

Marston uses the example of a river being turned by a wall or other barrier to help explain the emotion of Compliance. A river doesn’t hold its ground and fight against the barrier (dominance); it takes the path that it’s given (compliance). Marston states that compliance fits within the natural law of energy conservation. Force (energy) only has two options:

- Dominate

- Comply

The same river will continue to comply until whatever force is weakened enough to submit to the river. Until that point, the river is compliant with its station.

To understand compliance in humans, Marston looks to studies conducted with babies. Marston believes that compliance, like dominance, is taught. As an example, Marston details how babies will grab whatever is in front of them, including an animal or a fire. It is only after a certain number of painful experiences that a child will become compliant towards the environment they find themselves near..

Marston cites another study where adult subjects were asked to sit in a chair blindfolded. They were told that they were part of a study that was looking to understand breathing. What the women didn’t know was that once they sat in the chair, the researcher would be able to pull a lever that tipped the chair over. The subjects tried to ‘dominate their environment’ by yelling to the researcher or trying to escape the bounds of the chair. Once they realized that they couldn’t leave the chair, they submitted to their environment. The subject’s breathing reflected this as well. When the chair initially fell, their breathing was heightened. Once the subjects ‘complied’ with the situation, their breathing went back to normal.

It’s important to note that Marston believes compliance is a challenging and unpleasant trait to learn. Marston believed that compliance was often learned through pain. These two studies that Marston cited offer a glimpse into how he viewed this state of consciousness.

Characteristics of the Compliance emotion:

To help the reader understand what Marston means by the ‘emotion of compliance,’ he offers a list of words and characteristics to explain better how to identify this emotional state: “fear,” “being afraid to do,” “timidity,” “caution,” “weak will,” “conforming,” “swimming with the stream,” “open-mindedness,” “candor,” “being a realist,” “adapting,” “yielding to.”

The relationship between the Dominance & Compliance Emotions

Marston recognizes that the emotional response of Dominance and Compliance exist, at times, together. While these responses are at opposite ends of a spectrum, they can form a particular type of emotional response. To understand this relationship, Marston signals that active dominance is what is measurable and how we can determine the difference between the two emotional responses.

Marston uses the analogy of a ‘rat who is cornered will fight.’ A rat being in the corner is a compliant behavior because it is running away. However, when the rat recognizes that it is in a corner, the active dominance takes over the compliant response, and the rat fights. Marston concludes that dominance always replaces compliance.

Submission Emotion

Marston uses the example of gravity to explain his understanding of submission. Marston observes that all pieces of matter possess a form of ‘attraction’ which we call “gravitation.” Marston states that “the largest material body with which we come into daily contact [with] is the earth itself. The attractive power of the earth operates in alliance with the attractive force each smaller body exerts toward the earth.”

To Marston, this ‘alliance’ presents a perfect and objective picture of submission. While both objects exert force, one will willingly bend towards the stronger party. This ‘alliance’ allows both objects to remain close together in harmony.

Marston recognizes that Submission and Compliance might seem similar. However, Marston distinguishes these two ideas by offering that Submission is pleasant to learn and learning Compliance is unpleasant. In the chapter on Compliance, Marston offered that he saw compliance being ‘learned’ when a baby touched a hot object, or a woman became compliant to her situation when she was blindfolded and tipped over in her chair.

Marston believes that the learned trait of submission is readily evident in young boys in relationship to other young girls or their mothers. Perhaps he drew on his own youthful experience with his mother. Marston observes that boys’ behaviors towards women or young girls differ when he observes them with their fathers or other men. He details how young boys will obey commands from young girls and then immediately act rebellious towards their fathers.

It becomes clear that Marston believed submission wasn’t based on gender. Rather, society forces us to react a certain way depending on someone’s gender. As an example, Marston details an account of ‘Mr. H.’ and a young woman (who Marston failed to name) who both were principals of a school for troubled teenage boys. When these boys were caught doing something illegal (like boot-legging) the boys would become submissive towards Mr. H. However, when the young woman caught boys in similar positions, they would dominate her. Marston concludes that societal norms might be the deciding factor for when we choose to be submissive.

Characteristics of the emotion of Submission:

As with the other traits, Marston lists the following words to help describe the emotion of ‘Submission’: “docile,” “sweetness,” “good-natured,” “benevolence,” “generosity,” “tender-heartedness,” “being an easy mark,” “altruism,” “unselfishness,” “willing service.”

Inducement Emotion

Marston returns to an example of gravity to explain his understanding of the emotion he calls Inducement. Inducement is the powerful side of the alliance between a massive body and a smaller body as it relates to gravity. The larger body ‘induces’ the smaller body. Marston also uses the verb “attraction” to describe this action.

Babies showcase their ability to ‘induce’ their mother by holding out their arms or crying. If they are successful, the child will continue to develop their mastery of inducing others. Marston believes that babies are often more successful in inducing their parents than older children.

As children age, Marston notes how it’s easier to distinguish inducement from dominance by observing how children play. He watches that children will play ‘school’ or ‘house’, and they will exhibit the role of the person they are induced by. Marston believes that society ultimately pushes children towards a certain type of play, noting that boys will play ‘school’ or ‘house’ albeit reluctantly. He observes that often, boys will choose to play games that showcase their dominance over each other. Marston uses these examples to distinguish the differences between inducement and dominance further.

Interestingly, Marston notes how the emotion of inducement is particularly aligned with salespeople. He offers, “Selling goods is a clear-cut example of this type of composite emotional response (inducement). The salesman stimulates his prospective customers by impressing upon the buyer the financial advantage which particulars good hold. He also uses a considerable amount of ‘personal appeal’ to the buyer”.

Characteristics of the emotion of Inducement:

Again, Marston takes time to outline different words, phrases, and descriptions to help the reader understand the emotional state of inducement so the reader can better internalize their own familiarity with it. Marston offers the following words: “persuasion,” “attraction,” “captivation,” “seduction,” “vamping” (yes, acting like a vampire!), “convincing,” “making an impression on another person,” “alluring,” “luring,” “attractive personality,” “personal charm,” “personal magnetism.”

The relationship between the Inducement & Submission Emotions

To recap Inducement and Submission, Marston first reiterates the relationship between Dominance and Submission. Marston views these two emotions as opposites. He uses the example of a Mother and a child. Being weaker than the mother, a child learns to submit their ‘motor self’ to their mother. Additionally, the child will submit when the mother commands the child to do things like ‘hold on’ to an object or ‘let go’ of another object. The behavior of submission comes from positive experiences and safety.

On the other hand, inducement is the opposite of submission. It is a dynamic behavior. Inducement showcases an increased level of strength to secure the continued presence of a weaker person. While the terms ‘weaker’ and ‘strength’ are used, Marston affirms that these terms come from a relationship that resembles an alliance.

Marston reviews the relationship between a mother and a child and comments that the child commits to active submission when a mother successfully induces her child. This is seen when a mother gives a direction to a child (i.e. “hold on to that object”). If the inducement is successful, the child will behave as directed without issue.